I met with one of our Space Cyber Fundamentals instructors, Glenn Reynolds, this week at Keesler AFB. Glenn had a model of a Saturn V rocket on his desk and we got to talking about some space history events when it occurred to me that many of the students I was meeting were born after 2005 and probably had never heard the incredible story of the Skylab mission in 1973. After doing some math it occurred to me that this event may have unfolded before their parents had been born. After I muscled through that realization, I decided to revisit Jack Anthony’s excellent article. Heritage: pass it on.

“Moral of the story: Things don’t always go as planned. Really bad days may be salvaged with some out of the box thinking and “just getting on with it” — where “it” means finding new ways to reach the goal.” Paul S. Hill, former NASA Mission Ops Director, Shuttle Flight Director, author of the book “LEADERSHIP: From the Mission Control Room to the Boardroom” (See Video).

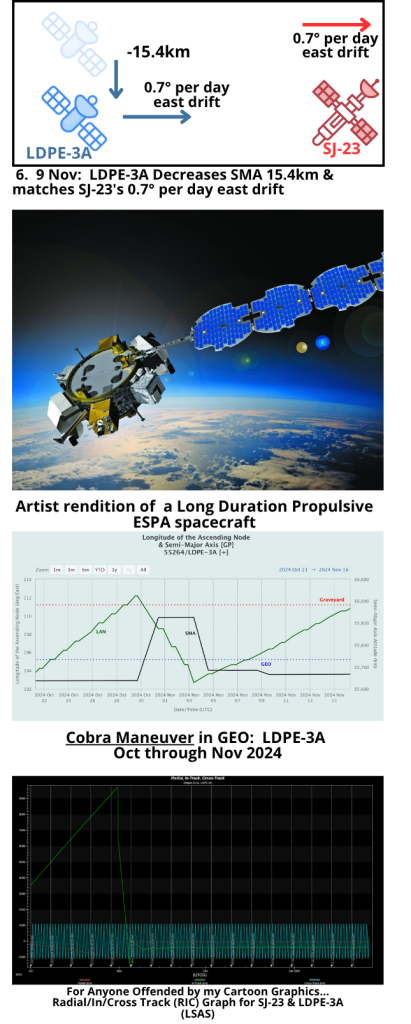

What was the first on-orbit satellite servicing mission? The repair and on orbit maintenance of the Hubble Space Telescope is perhaps what you’ll hear most folks answer. It was a remarkable feat to send Space Shuttle crews to Hubble to correct Hubble’s “eyesight” and then over the years complete upgrades and part replacements. It’s an awesome story! However, in my mind, the first satellite servicing mission was Skylab in May 1973. Let’s learn more…it’s a story of grit, determination, creativity and a few dramatic demonstrations by the astronauts of Newton’s 3rd law….read on!

Skylab was launched 14 May 1973. It was America’s first space station. The modified Saturn V headed skyward and at one minute into flight an electrical glitch causes a premature deployment of the Skylab’s micrometeoroid shield. That was not suppose to happen until it reached orbit. This also ripped away one of the 2 solar arrays. In the melee, the other solar array was sprayed with debris and pinned to the side of the station. It was unable to be deployed once in space. Skylab made it to orbit and within a few orbits the Mission Control folks knew something was very wrong. Telemetry showed no electrical power being generated by the solar arrays and the internal temperature of the Skylab was HOT! The first crew of Peter Conrad, Paul Weitz, and Joe Kerwin would have to wait beyond the scheduled 15 May launch to go dock with Skylab. The next 10 days was a race against time. Skylab was ailing and they needed to get to it and help save it before the damage would make it uninhabitable. Great minds came up with plans, devices and procedures to fix Skylab.

On 25 May, the crew launched into orbit. Stuffed into their Apollo Command Module was all sorts

of materials, tools, ropes and things they would use to repair Skylab. They completed a

rendezvous with Skylab and did a fly around. The first views were disheartening. They confirmed

one solar array was gone, the other jammed in a closed position, and the micrometeoroid shield

was gone. Skylab was being cooked by the Sun, the external surface of the station was blistering

from direct sun effects. Yikes, the astronauts needed to get to work.

First, they “soft docked” with Skylab. This was to connect the Command Module but not lock it

into place. With the spacecraft de-pressurized, Paul Weitz stood up in the open door with Joe

Kerwin hanging onto his ankles and Weitz tried to use a 4.5 m pole with something that looked

like a modified tree lopper on the end. They relentlessly tried to free the remaining and very

stuck solar array. No Go. A closer look showed there was a mess of shield debris that would

have to be removed to deploy the array.

Then they attempted to “hard dock” with Skylab and lock the two spacecraft together. That ran

into some problems, the holding device would not fire. Like Maytag repairmen, they worked on

the docking system hardware in the Command Module nose section and jerry-rigged a fix. They

gave it another try and eureka, they were hard docked. Time to get inside Skylab. The large

workshop section inside temp was 130 degrees F.

Next, they had to get a reflective mylar-like sun shield over the part of the external Skylab

where the shield was to be. The shield had many purposes, including insulation from the sun’s

heat from transiting into the station. There was another section of the Skylab not as hot, so the

crew did find refuge from the steaming workshop there or actually back in the Command

Module. There was a way to access space via an air lock, a tunnel that enabled them to deploy

things into space. So, they brought with them a parasol, a mylar reflective umbrella looking

thing. They were able to push the parasol through the airlock and get the device unfolded to

then protect the skin. Hooray, the temperatures in the workshop started to cool. OK, so this

install and deploy parasol fix went AOK. Now to get solar array deployed.

Astronauts Conrad and Kerwin performed a spacewalk. Their plan was to use bolt cutter type

devices to cut straps and free the array which was pinned up against the Skylab’s side. They

assembled six 1.5 m rods (made a long pole), attached cutters and Kerwin worked hard to get

the cutters in place on straps that held the array and was jammed by debris from the 1-minute

into launch anomaly. Kerwin diligently got everything in place but struggled. He tried to pull the

lanyard to activate the cutters, No Luck. So, here’s where the repair job gets exciting. Do you remember Newton’s Third Law (Action-Reaction)? Well, Conrad went over to take a peek at the set up. Upon his arrival, the cutters suddenly fired and freed the solar array to a 20-degree deployment (they needed 90 degrees). But, the array bonked into Conrad and in his own words sent him “ass over teakettle” (my pardon, but that’s what he said). Thankfully he was tethered and didn’t go off into space. Whew.

The array was deployed 20 degrees, 70 degrees to go to get it fully deployed. Conrad worked his way to stand on the hinge part, rigged a tether over his should and just like when you use a strap to help lift things, he stood up and Kerwin joined in pulling on a tether. WHAM, the solar array released and travelled to final 90 degree position. Of course, Isaac Newton had a say and both astronauts were catapulted away from the now deploying solar array. Good news, they were caught by their tethers and not propelled into space. The solar array was deployed and soon working, the overall output power from a small set of arrays that deployed OK after launch and this big array went from 40% to 70%. Yay!

Thus, Skylab was revived/saved, the temperatures inside were manageable and the power adequate for the planned year-long US space station operations. From May 1973 to February 1974, three crews of three astronauts work on the Skylab. It didn’t look exactly as planned and was a little shy on full power, had a funny gold-ish thing covering it, but the first crew saved the Skylab with this amazing first ever on orbit servicing and repair. Future crews would further help repair Skylab more so. There you have it…the first ever on-orbit repair- Skylab 1973 Skylab would eventually re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. On July 11, 1979, with Skylab rapidly descending from orbit, engineers fired the station’s booster rockets, sending it into a tumble they hoped would bring it down in the Indian Ocean. They were close. While large chunks did go into the ocean, parts of the space station also littered populated areas of western Australia. Fortunately, no one was injured.