Analysis of Developments in the Space Domain

23 Feb 2023: China sent the Zhongxing-26 (ChinaSat-26) communications satellite into orbit on a Long March 3B rocket from Xichang. It was China’s first launch after a 39-day pause for the Chinese New Year. ChinaSat-26 is in geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). Launch Video.

– ChinaSat-26 is based on the DFH-4E satellite bus and uses chemical and electric propulsion. It is China’s first satellite providing more than 100 gigabits per second (Gbps) throughput and developed by CASC’s China Academy of Space Technology (CAST).

– CAST states the satellite is equipped with 94 Ka-band user beams. This is 3.5 times more than the 26-beam, 20 Gbps, Dongfanghong-3B-based Zhongxing-16 launched in Apr 2017.

– ChinaSat-26 will mainly provide broadband access for fixed terminals and aviation/shipborne users in China and surrounding areas from 125°E in the geostationary belt.

– The launch was China’s first since 15 Jan, when launch activities were paused for the Chinese New Year.

– It is the fifth Long March launch this calendar year, with CASC planning more than 60 launches in 2023. Various Chinese commercial companies plan to add 20 or more launches to the overall figure. <editor comment: uh-oh>

– CASC is developing a 3rd generation high-throughput satellite with capacity >300 Gbit/s.

– These particular ChinaSat spacecraft are for civil use, different from Chinasat-1 series, which are believed to be military satellites.

– ChinaSat satellites are owned by China Satellite Communications. They are communication satellites produced to serve several different communication purposes for China. They provide reliable, high-bitrate uplinks for radio and TV stations.

24 Feb 2023: China launched a Long March 2C rocket from Jiuquan carrying what is believed to be an Egyptian Earth Observation satellite Horus-1. There are very few details available about the mission and capabilities of Horus-1. The altitude, 500×485.5kms and inclination 97.5° places Horus-1 in sun-synchronous orbit (SSO), an orbit most frequently used for earth observation.

Launch Video.

– China did not opensly disclose the owner/operator of Horus 1 (also known as Helusi 1).

– It is likely an Egyptian earth observation satellite, which was jointly built by Egypt’s National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences (NARSSS) together with the Chinese company DFH.

– Egypt contracted with China for a 330kg imaging satellite called MisrSat-2 (not to be confused with the MisrSat-2 launched in 2014, they seem to have restarted the numbering scheme); possibly Horus-1 is just a new name for this satellite.

-There is open source reporting on a scheduled Dec 2022 launch of Misrsat-2. The Misrsat-2 mission was to measure the climate considerations of African countries. It was assembled in the Egyptian Space City near Cairo.

– In addition, the design of the mission patch mentions the “One Belt One Road Initiative,” referring to the Chinese initiative to build transportation and trade links throughout Asia, Europe, Africa, and the world.

– Finally, China also displayed a foreign flag announcing the success of the launch from Yemen which bears a close resemblance to the Egyptian flag.

14 Feb 2023: It appears all 27 Yaogan-35 (15) and Yaogan-36 (12) satellites have reduced their altitudes. In the Yaogan-35-2 formation, one of the satellites (Yaogan 35-2C) has fallen out of the typical formation and is now far ahead of YG-35-2A/B.

– Yaogan-35-2C (YG-35-2C) semi-major axis (SMA) value is now tracked at 485.9km (21 Feb 2023). Its partner satellites, YG-35-2A and 2B both have closer SMAs (493.6 and 493.8kms respectively.)

– As a result, YG-35-2C is now much further in the “lead” of the three satellites. The YG-35-2 triplet no longer matches the formation of any of the other YG-35 or 36 trios.

– YG-35-2C has reduced SMA 11.3km, nearly triple the reduction from YG-35-2A (4.8km) and YG-35/2B (4.2km). YG-35-2C’s station keeping pattern also differs from other YG-35 satellites. The satellite could be having operational anomalies.

– For their part, YG-35-2A and YG-35-2B also appear to have further separation than their counterparts in the constellation.

– All of the Yaogan 35 and 36 satellites appear to have reduced their SMA. Without knowing the mission or capabilities of the satellites it is difficult to speculate the rationale behind the maneuvers.

– The reduction in SMA for the other 24 YG-35 & 36 satellites ranges between 4.6 and 5.1kms.

– As of 24 Feb 2023 all satellites continue to decrease their SMA.

21 Feb 2023: Beginning in mid-Nov 2022, TJS-3 began drifting eastward. In late-Jan the satellite increased its altitude to rejoin the GEO belt. It is now holding steady at 137.5° E. It is currently in the vicinity of (IVO) the US Advanced Extremely High Frequency System (AEHF)-6. Since its launch on 24 Dec 2018 TJS-3 has frequently maneuvered and displayed unusual behavior for a GEO-based satellite. Its maneuvers seem to have placed it in the vicinity of several US military communications satellites.

– There is little public information available regarding the TJS-3’s mission. There is the launch video from 2018 and an excellent COMSPOC video from 2020.

– The COMSPOC video describes the unusual interaction between TJS-3 and its Apogee Kick Motor (AKM) shortly after arriving in GEO.

– There is speculation that TJS-3 might be a military SIGINT or early warning satellite. The satellite is reportedly built on the SAST-5000 all electric bus and features a multi-frequency and high speed communications payload.

– TJS-3 began its latest maneuvers in early July 2022 and has made brief stops near US Military COMSATs WGS F4 (USA 233) and AEHF-6 (USA 298). As of 22 Feb, TJS-3 remained IVO AEHF-6.

– IVO is a very loose term since to date the closest approach between TJS-3 and AEHF-6 has been 181.35km.

– WGS F4 is a US military communications satellite as part of the Wideband Global SATCOM program, launched in 2012.

– AEHF-6 is a military communications satellite. AEHF-6 was launched in 2020 and completed the AEHF constellation of 6 satellites.

– Since its arrival at GEO in 2018, TJS-3 appears to have visited other US satellites, primarily COMSATS.

– The earliest instance was with MUOS-4 for over a year, then with Quasar 13 (US Relay satellite).

– TJS-3 first visited WGS F4 in early 2021 and remained in the area for several months. It then rejoined its AKM later in 2021. While it may be an erroneous reading, it appears TJS-3 briefly maneuvered to the vicinity of USA 118 which is speculated to be a US ELINT or SIGINT satellite.

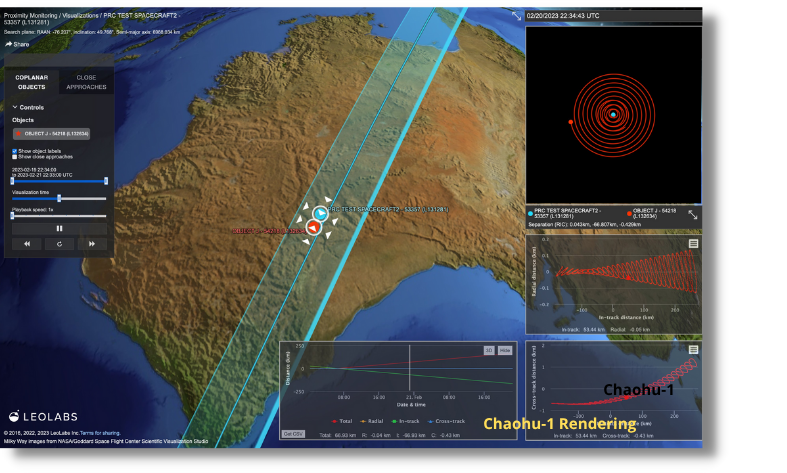

21 Feb 2023: LEOLabs, a private space domain awareness company, reported its radar systems detected a newly released object from the Chinese spaceplane. It is not clear if this is a new object or the same “Object J” first reported in Spacetrack.org in late-Oct 2022. In Nov 2022 “Object J” was within 100m of the Spaceplane. It is possible the two rendezvoused and then Object J was re-released.

-Observers also noted a .7km decrease in the Spaceplane’s apogee and perigee on 20 Feb. The Spaceplane returned to its previous altitude on 21 Feb.

– China carried out the second launch of its “reusable experimental spacecraft” from Jiuquan in the Gobi Desert atop a Long March 2F rocket Aug. 4. As of 26 Feb it has been in orbit 206 days.

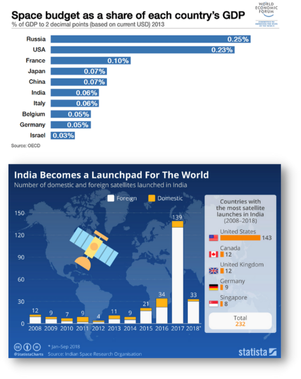

13 Feb 2023: Pranav R. Satyanath authored an excellent 2 part examination or India’s current space policy and recommended evolution (hint more satellites, less kinetic ASAT tests).

– India abstained from voting on the United Nations (UN) resolution to ban debris-creating direct-ascent anti-satellite (DA-ASAT) testing.

-India’spolicymakers and government officials have provided very little clarity about India’s space security policy since it conducted its DA-ASAT test in March 2019.

-India has historically supported outer space arms control and risk reduction measures, even though it has not put forward concrete proposals and approaches to tackle space threats.

-India was a proactive participant in the UN’s Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) agenda of the 1980s. This period was marked by New Delhi’s criticism of US President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) and its vocal opposition to the militarization and weaponization of space more broadly.

-In 1986 India called on the United States and the Soviet Union to halt all testing of anti-satellite (ASAT) capabilities and eventually ban ASATs.

– After the India’s own overt nuclear tests of May 1998, it’s politicians saw the need to develop limited ballistic missile defense systems around the national capital. At this point there was a slow and subtle shift in India’s space security policy.

– After China’s ASAT test in 2007…India’s defense and scientific bureaucracies slowly galvanized support for India’s own ASAT capability.

-India’s exclusion from the 2013 Group of Governmental Experts also made it recognize the premium placed on its status as a space power. The DA-ASAT test of 2019 was a symbolic demonstration of India’s ascent as a space power with expanding geopolitical interests.

– India’s space security policy consists of three distinct elements: (1) the need for legally binding instruments in space; (2) openness to negotiating non-discriminatory, universally-applicable transparency and confidence-building measures (TCBMs) that could complement legally binding instruments and; (3) aversion to purely non-legally binding measures, which are deemed ad-hoc and non-universal.

– These preferences have also driven India to abstain from voting on the US-led test moratorium as the resolution does not address the legally binding aspects of the proposed test moratorium.

– In 2020, the government opened the space sector to private industries, signaling Indian policymakers’ willingness to embrace the new space age, where space technologies play a crucial role in achieving national developmental goals.

– In Feb 2022, the Indian Air Force (IAF) released its new doctrine where it envisions transforming itself into an Aerospace Force and taking greater responsibilities in the space domain.

16 Feb 2023: A group of 17 European nations, plus the US and Canada announced a plan to share intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance data from satellites — spurred by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine that highlighted the value of space-based remote sensing for warfighting..

– Under a letter of intent, the nations will launch the Allied Persistent Surveillance from Space Initiative (APSS) to explore “the potential for sharing data from national surveillance satellites; processing, exploitation, and dissemination of data from within national capabilities; and funding to purchase data from commercial companies,” according to a UK Ministry of Defence press release.

– The letter was signed by Britain, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey, Sweden and the US. All are NATO members, with the exception of Sweden, which has asked to join.

– APSS will be ‘sensor-agnostic and solution-agnostic”; it will be open to all existing – and future – space assets, regardless of their scope, technologies and

specificities. It will bring together both government-owned and commercial space assets.

– Ukraine’s successful use of remote sensing satellite data, primarily but not exclusively provided to Kyiv via the US commercial providers at the urging of the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency and the National Reconnaissance Office, to assist its military in both keeping tabs on its own dispersed forces and in targeting Russian forces has resonated with other nations around world. In fact, NATO has been considering whether it should begin buying commercial remote sensing data collectively.

– From the NATO announcement: At NATO, space plays an important role in the operational military domain to navigate and track forces, detect missile launches, but also to ensure effective command and control and communications. To continue to ensure effective deterrence and defense while retaining its technological edge, the Alliance needs to leverage on both national and commercial technologies and assets in the space domain.

-Primary APSS Objectives are: 1) achieve ‘persistent surveillance’, that is allowing NATO to collect data on any location at any given time; 2) increase space-based intelligence sharing across the Alliance, leading to a more comprehensive cross-domain intelligence picture necessary to inform political-decision making and military operations; and 3) improve NATO’s overall intelligence through a more effective use of both government-owned and commercial space-based assets, technologies and data

-The new persistent space alliance is expected to start operating in 2025.

-The NATO Space Centre began operations from Germany in early-2021. Here’s a video showing the facilities and featuring interviews with several allied officers.